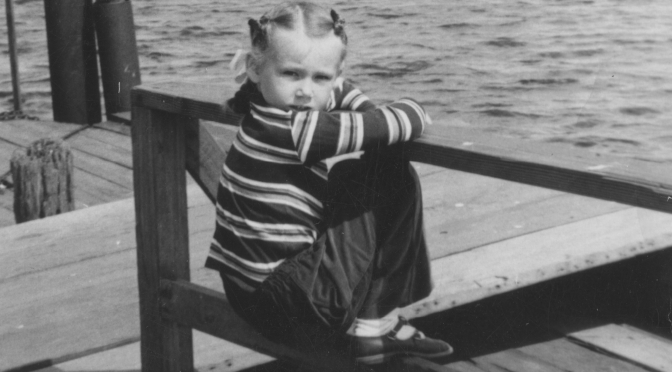

Me (front, second from left) and my friends at Latvian camp in Michigan.

I always assumed that I would live long. After all, my maternal grandmother, who survived the Russian Revolution as well as World War I, World War II, the resulting diaspora and emigration to the United States, died when she was 90. And my mother, who saw much of that herself, died when she was 91. Since life expectency has increased substantally since my grandmother’s day—she was born in 1879, when it was about 43 years for Baltic females—and was longer for females in the States than for those left in Latvia and since we arrived in the States when I was just five years old, I figured that should count for something. So, it seemed likely that the combination of good genes and good healthcare here would do me well.

I also assumed that most people—my mother and grandmother included—underestimated the toll that being a displaced person nearly from birth had taken on me and the other Latvian girls that I knew growing up in Grand Rapids. By all appearances, my cohort and I were remarkably healthy. But I felt that I was—and suspected that they might be, as well—damaged in ways not apparent to those who did not care to see. Of course, I meant emotional or behavioral–not physical–damage, conveniently forgetting that I considered mind-body dualism something that should have died with Descartes. So I saw nothing incompatible in the two assumptions. We might have to struggle more but would still lead long, productive lives.

That lasted as long as 2012, when I learned that one of the Latvian girls (the one directly behind me in the photo) was having a double mastectomy. Although she responded well to treatment, it made me question one of my asumptions. Particularily when another girl (the one to my right) succumbed to ovarian cancer in 2016. She, like me back then, was in her early 70s and her mother had lived to be 92.

That forced me to face the fact that my nearly dying a year earlier, when I was 71, might not have been the anomaly that I made it out to be (see “Body Language”). Particularly since the extensive testing I underwent in the process revealed a range of other issues. All I needed was the sad news that yet another girl (the one on the right in the back row) had died of unknown causes after six days of hospitalization. She was also in her early 70s while her mother had died a few years before at age 93

In all cases, death or potentially deadly health conditions had occurred about two decades before they should have according to my first assumption. While I know nothing about the remaining two girls, it did make me wonder whether I would last to 2035, as I had previously expected. And whether the stress of displacement at an early age might have done more than merely make me quirky.

So I searched for corroborating data. Not surprisingly, there was little that was even remotely relevant. One longitudinal study on the forced migration of Finnish children was about all that I could find. In reviewing the existing literature, the authors cited research, particularly from the United States, that showed better health among most immigrant subgroups than native-born residents as measured by indicators such as mortality, morbidity or self-ratings.The immigrant advantage could be attributed to selective migration, meaning that migration, especially the long-distance type, is dominated by people whose health is better than that of the origin country population.This is further reinforced by some stringent host country screening processes. Whether children who move with their parents are subject to the same selection mechanisms is less clear.

Selective migration was intentionally ruled out in the study itself since all families from a specific location were forced to move. As was selective return migration, where unhealthy migrants or those who experience deteriorating health tend to return to their communities of origin. Here, none of the families could return after World War II since their land had come under the control of the Soviet Union.

No support was found for the hypothesis that the traumatic event of forced migration during childhood has long-term negative health consequences. In fact, adult child migrants had lower odds of receiving sickness benefits and the females also had lower odds of receiving disability pensions. And mortality rates were largely driven by patterns specific to eastern-born populations of Finland. The authors suggested that the absence of adverse health effects could be due to the successful integration of these child migrants into post-war Finnish society.

As a former researcher, I knew that this study was hardly definitive. It is widely accepted that negative results are easier to obtain than positive ones since there are so many confounding variables. I also knew that the five or so years of displacement in foreign nations as well as the eventual insertion of young Latvian children into an unwelcoming American culture was, at best, only loosely comparable to the Finnish experience. Still, I took it as a sign that I–unlike others in my cohort–was not doomed to an early death.

That worked reasonably well until this past June, when I was diagnosed with Stage 3 triple-negative invasive breast cancer. I could not understand how on Earth this had happened. No one in my family had ever developed cancer of any sort apart from my aunt in London, who was a dentist and attributed her melanoma to the careless way X-rays were initially used in her profession.

All I could come up with was that my deterioration was but one manifestation of the general breakdown we had all experienced over the past few years. Where things dating back as far as my grandmother’s day–pandemics, far-right extremism , Russian invasions and the subjugation of women–that I thought had been relegated to the trash heap of history had re-emerged. That all the progress we had seen in our lifetimes had eroded and done damage to me just as it had when I was a one-month-old war refugee.