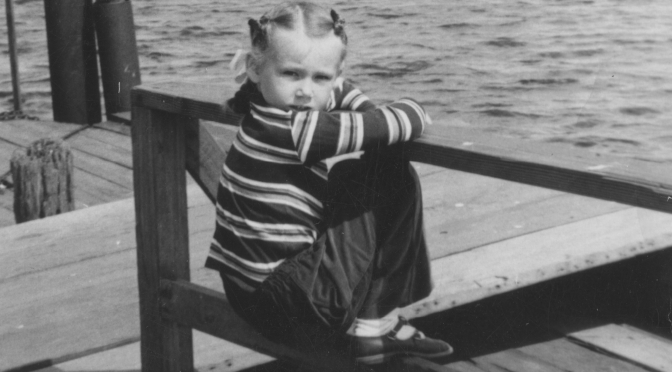

Me in my standoffish mode, sitting on a dock at Reeds Lake in East Grand Rapids, Michigan during the early Fifties. (Photo: my mother, Elsa Jurgis)

The most fun I ever had with my mother occurred after she came to live with me in Maryland following my father’s death. We often did silly stuff. Sometimes I made up songs or modified existing ones to suit the situation. (Neither of us could carry a tune, so it worked out well.) In my car, I would sing “Seven Little Girls Sitting in the Backseat” each time she said something like, “Keep you mind on your driving, keep your hands on the wheel / Keep your snoopy eyes on the road ahead.” Once I got to “Kissin’ and a huggin’ with Fred,” I tickled her stomach. “Don’t touch my private parts,” she said. “What are your private parts?” I asked. “All my parts are private parts,” she said.

I recently related this anecdote to my niece, Mara Miske, who found me a few years ago through this site. Although we had never met and she was decades younger, our connection was immediate. And, much as we insisted that we were not real Latvians, both her parents and I were that by birth and it accounted for much of our natural rapport. And why it was harder to achieve with those who had negligible ties to our native land. The latter became abundantly clear while she was coaching me on how to approach the middle-aged man who likely was the baby that 21-year-old me gave up for adoption at birth and whom Mara had located through DNA data posted on the My Heritage site. Being the more maternal of the two of us, she said, “Give him the warm-and-fuzzies he needs.” After which we laughed, knowing that most Latvians are simply not wired that way.

Not that Latvians are cold, although I have certainly heard that said. And read about a study–led by a researcher from Michigan State University, of all places–that ranks Latvia and other Baltic States near the bottom on empathy. Rather, it seems to be hard to find the right word. One that gets the point across without being perjorative is”self-contained,” which is defined as “quiet and independent; not depending on or influenced by others.” Another is “introverted.” Some liked that one so much it became the basis of a long-running, award-winning campaign–#IAMINTROVERT–to promote Latvian literature. (Never mind that it was launched at the 2018 London Book Fair, where the market focus was on the Baltic states, including Latvia, and where the large crowds and absolute unavoidability of social interaction must have made it an introvert’s worst nightmare.)

While the campaign gently pokes fun at what could be considered a national trait, it also highlights some positive aspects. Namely, that there is a link between a preference for solitude and creativity. In one article, Anete Konste, a humorist integral to the campaign’s success, notes that introversion is prevalent among authors, artists and architects as well as others working in creative fields. The piece goes on to state that psychologists have suggested that creativity is an important part of Latvian self-identity and, as such, a priority in the government’s educational and economic development plans. The European Commission has thus reported that Latvia has one of the highest shares of the creative labor market in the European Union.

How Latvians got that way, of course, is anyone’s guess. If pressed, I would say that it started with some particularly brutal forms of natural selection: the wars, occupations and displacements that have plagued the Baltic region throughout history. The introverts–or, as I prefer, the self-contained–kept their heads down and their emotions in check, trusting only themselves. Thus, while my maternal grandfather was murdered by a paramilitary mob during the Russian Revolution for defending his factory (see “The Face-of Extremism”), my maternal grandmother, pregnant with my uncle, quietly took my two-year-old mother back to Riga, sold sausages on the street until she turned herself into a successful business woman and–two world wars later–died in a hospital bed in America at age 90. A lesson my mother, who played her cards close to her chest, learned very well.

The trick is getting others to understand. Both the horrors that you have encountered and the damage they have done. My mother’s solution was to not even try. Her experience was so far removed from that of her American acquaintances that she let them believe what they wanted. Which, once she arrived here in Maryland, was that she was a cute old lady from somewhere they could not quite place. Every morning for years she–legally blind and crippled by arthritis–and her English Springer Spaniel walked the steep, winding loop that took her to her beloved Trolley Trail and back again. I feared for her safety, especially after the dog died, but refused to leave her staring at walls while I went to work in DC. Somehow, she always attracted a crowd. And, inevitably, someone would say, “You have an interesting accent. Where are you from?” And my mother would say with a smile that only a few would see as anything but sweet, “Michigan!”

I emulated my mother until I was17 or so. Then, while having a hard time writing a paper on “The Waste Land,” I downed most of a bottle of vodka, lost consciousness in a pool of vomit and was taken by ambulance to an emergency room in the dark during a blinding snowstorm. (See“Winter Wonderland.”) Perhaps binge drinking–so common in Latvian social circles when I was growing up–is as instrumental as solitude in turning introverts into creatives. All I know is that after the ranting and raving I did alone in my second-story room while falling-down drunk, I found my own voice. And, decades later, after I retired and my mother died, the time to devote to writing essays and stories and novels and, eventually, the development of this site. I truly believed that if I could find the right words to string together, the world would come to understand me. Even my long-lost son would, once I gave him his family history. (See “Why I Write.”)

Whether my communication style made me better understood than my mother is up for debate. Particularly when it comes to inferring my feelings. Take the case of the man who might be my son. (The qualification only means that a definitive maternity test conducted by a certified medical laboratory has yet to be done.) Before Mara could school me on warm-and-fuzzies, I had inundated the poor guy with data designed to quickly fill the gap left by my decades-long absence. Posts and pages from this site, published and unpublished works and material that I generated just for him. How was that to be taken? How would you know without being told that the poem about loneliness and the sea written by the the cartoon character of an introverted Latvian below started as an attempt to write a love letter?

NOTE: To read more about my own self-contained writing style, see “A Formal Feeling Comes.” And for more on one of my minor contributions to Latvian literature, see “A Book About Sentient Beings, Great and Small.”