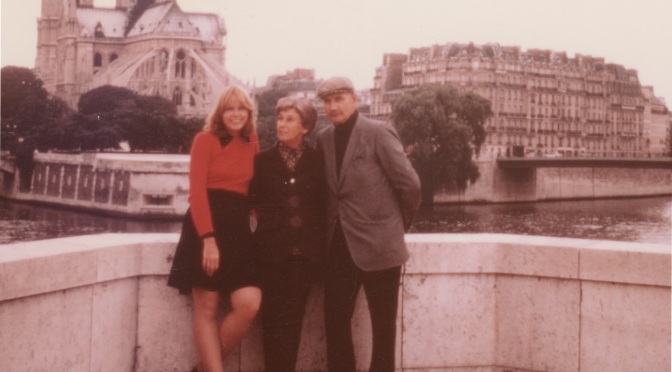

My parents and me by the Seine in the Seventies. (Photo: Duncan R. Munro)

Growing up, Paris was my place of dreams. Particularly the Paris of immigrants and expatriates. The Russian Vladimir Nabokov, the Polish Frédéric Chopin, the Belgian Georges Simenon, the Dutch Vincent van Gogh, the Austrian Amadeus Mozart, the Hungarian Franz Liszt, the Romanian Eugène Ionesco, the Italian Amedeo Modigliani, the Spanish Pablo Picasso, the Irish Samuel Beckett, the English (but India-born) George Orwell, the West Indian Camille Pissarro, the Chilean Pablo Neruda and countless Americans, from Josephine Baker to Ernest Hemingway to James Baldwin to Jim Morrison. And many more foreigners who lived and sometimes died in The City of Light. All made me think it could be where I, a displaced person, could finally find the kind of creative environment that I intensely craved.

I got to Paris while still in my twenties, but not alone. And not to stay. I was with my then husband as well as my parents. Moreover, my mother, normally an avid tourist, had taken a tumble down a flight of stairs at my aunt’s house in London, so we had to help her along. And there was the usual British baggage-handlers’ strike, so we had to lug our own. And we made the Dover-to-Calais overnight crossing on a hovercraft that segregated sleeping quarters by sex, so my husband and I elected to wander around the boat all night instead. And what seemed like every single person on the crowded train to Paris had a heavy nicotine habit, so that even a smoker like I was back then could barely breathe. So all we wanted once we arrived was to head for bed.

But Paris would have none of that. She provided us with a chauffeur de taxi who exuded joi de vivre. He loved life, he loved Paris and he was determined that we do the same, despite any unpleasantness that we had experienced earlier. So we spoke French, or what passed for it on our part—he was probably the only person that we encountered who did not switch to flawless English after a few of our clumsy sentences—and we started to smile, then to laugh. Looking back at us far more than in the direction he was driving, he pointed out each monument, each building of any importance and even the occasional interesting cul de sac. And a tree or two, warning us that, since it was October, we should expect many large chestnuts to rain down on our heads. By the time that we arrived at our hotel, there was really no question of napping. The only debate that we dealt with was which of the nearby bistros and cafés we would select to while away the rest of our day.

Over the subsequent days, we spent as much time in the streets and shops and restaurants as we did in the museums and galleries. But wherever we went, we—three Latvian-born and one Scottish-born Americans—were accorded the same consideration, invited to share the same joy evidenced by that taxi driver. We stumbled upon a nondescript restaurant, for instance, somewhere between the Père Lachaise Cemetery and the Moulin Rouge, and decided to stop for lunch. Inside, it was indistinguishable from many of the high-end restaurants my husband and I encountered in Boston, except it was frequented mainly by locals. Our waiter pointed out an elegant gray-haired man who came in daily and took two hours to enjoy his midday meal. This waiter also stopped in the middle of taking my mother’s order to bring her a plate of little raw fishes so that she could see what she would get lest she regret selecting an unfamiliar rouget dish. And thereafter brought everyone else’s orders to our table first so that we could better understand what constituted French cuisine.

I remember that taxi driver and that waiter each time that I hear “The Last Time I Saw Paris.” And, since the November 13 terrorist attacks, that song has played constantly in my head. You see, it was composed in 1940 and inspired by the Fall of France, which brought Paris under Nazi Germany’s control. And seems terribly relevant these days since it gives voice to the sadness that comes when a wonderful way of life is suppressed by, basically, barbarians. The lyrics nostalgically recall the dodging of taxi cabs and the sound of their horns. The laughter in the heart of Paris heard “in every street cafe.” The “trees dressed for spring,” when the chestnuts that we saw would be abloom with magnificent creamy pyramids. It does not say, because, of course, no one knew then, that Paris would be back. But it happened in a matter of years, and it will happen sooner now, once she has mourned her loss. After all, she has had the same motto since 1358: “Fluctuat nec mergitur,” which translates to “Elle est agitée par les vagues, et ne sombre pas,” which translates to “She is tossed by the waves but does not sink.”

In the aftermath, as attempts are made to protect her from further assault, I wonder whether my youthful dream of Paris as a site where displaced persons of all sorts can thrive will survive unscathed. Prior to the current attacks, Paris was one of the most multi-cultural cities in Europe. According to the 2011 census, 20 percent of the population was foreign-born. The areas where these attacks occurred were—and perhaps not by accident, as some suggest—vibrantly multicultural and replete with a variety of places where all people could enjoy themselves. I remind myself that terrorism is nothing new. The Seventies, when my family and I were in Paris, was marked by events such as the Munich massacre at the 1972 Summer Olympics; the bombings, kidnappings and murders by European militant organizations such as the Red Brigades and the Baader-Meinhof Gang; the IRA bombings in Britain; and violence by American groups such as the Weather Underground and the Symbionese Liberation Army. But neither, alas, is xenophobia and scapegoating during times of trouble.

“The Last Time I Saw Paris,” a song composed by Jerome Kern with lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, published in 1940 and sung by Kate Smith.